The Blank Caught Fire

August 7, 2013 at 11:40 am | Posted in personal, poetry | Leave a comment I realized this morning that I haven’t yet told this blog about my new online poetry project, The Blank Caught Fire. It started in April as a National Poetry Month project, and after succeeding at writing 30 poems in 30 days (!), I’ve been continuing it at a more leisurely pace. It’s a collage poetry project, where my source material is my partner’s current online writing project, Sister CIty 73. His project is a serial, improvisatory, weirdo novel wherein the plot moves forward through a combination of random chance (literal throws of the dice), bibliomancy (looking back at previous pages for fortuitous juxtapositions), and a fascinating kind of associative logic wherein the figurative images that have been used to describe a character in the past will dictate her present actions. For example, when a character receives a telephone call summoning him into a room full of people he knows are angry at him, he hesitates, but since he has been compared to a dog before, he comes when he’s called. These strings can get much weirder, such as when a character is compared to another character’s teeth, and that character been compared to an actress, “so her teeth / are good and so he is / good which is what Erin / says Superman / does so he’s flying.” You’ll note the reference to myself there; I’m occasionally consulted as an oracle for this piece (along with the dice, the book itself, and the previous images), and some of the author’s day-to-day experience is also woven in. It’s super fun!

I realized this morning that I haven’t yet told this blog about my new online poetry project, The Blank Caught Fire. It started in April as a National Poetry Month project, and after succeeding at writing 30 poems in 30 days (!), I’ve been continuing it at a more leisurely pace. It’s a collage poetry project, where my source material is my partner’s current online writing project, Sister CIty 73. His project is a serial, improvisatory, weirdo novel wherein the plot moves forward through a combination of random chance (literal throws of the dice), bibliomancy (looking back at previous pages for fortuitous juxtapositions), and a fascinating kind of associative logic wherein the figurative images that have been used to describe a character in the past will dictate her present actions. For example, when a character receives a telephone call summoning him into a room full of people he knows are angry at him, he hesitates, but since he has been compared to a dog before, he comes when he’s called. These strings can get much weirder, such as when a character is compared to another character’s teeth, and that character been compared to an actress, “so her teeth / are good and so he is / good which is what Erin / says Superman / does so he’s flying.” You’ll note the reference to myself there; I’m occasionally consulted as an oracle for this piece (along with the dice, the book itself, and the previous images), and some of the author’s day-to-day experience is also woven in. It’s super fun!

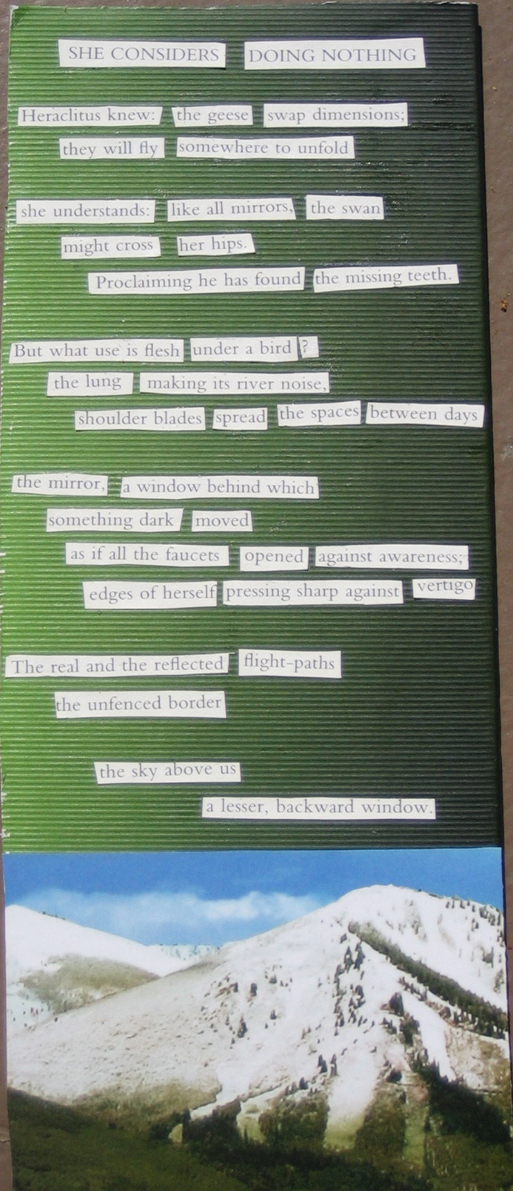

So as you’ll notice if you followed any of those links, Sister City 73 is written in columns, and that’s where my collage work comes in. Each of the poems in The Blank Caught Fire is based on a single page of Sister City 73, and is assembled out of the fortuitous phrases that are generated where words rub shoulders with one another due to the columnar format of that project. I’ll post two of my favorite poems below, and if you like them you should consider checking out the project on Tumblr and/or buying the chapbook from Horse Less Press that collects some of the early poems!

—

only pretends to be

something like a room I go to

I puzzle about one

splatter of himself

the Chinese fire

has a wealth of words

in the case of old images

I brush by ten years—

the coin says it’s two:

the next lover’s

sputtering trick birth

—

don’t bother asking skatespeare

it’ll probably be called

“studies: figurative and then crushed”

my memory back under the stage

with all the repetition

tempts me with accident

the opposite sister

in love with the Shakespearean

who has taken up with his hero

in a plan to redeem his rival

and since her embodiment shows

he lost to her wooden impression—appropriate

in the battle of Frank O’Hara

lucky for him, she’s also the perfect wave

transformation is as fickle

from figurative to literal—ah, Romeo!

Traffic and Weather Forever

November 16, 2010 at 1:17 am | Posted in attention, boredom, contemporary, excess, personal, poetry, repetition | 4 CommentsI am currently reading Kenneth Goldsmith’s Traffic, a conceptual poetry project consisting of twenty-four hours of traffic reports from New York’s 1010 WINS (available online in its entirety here), and am stunned to find myself moved nearly to tears. Goldsmith, who claims that his transcription projects make him “the most boring writer that has ever lived,” is not thought of as a particularly moving writer, and I was certainly not expecting to react this way. But as soon as I opened the book I was floored; I was transported Proust-style right back into the kitchen of the house where I grew up in suburban New Jersey:

12:01 Well, in conjunction with the big holiday weekend, we start out with the Hudson River horror show right now. Big delays in the Holland Tunnel either way with roadwork, only one lane will be getting by. You’re talking about, at least, twenty to thirty minutes worth of traffic either way, possibly even more than that. Meanwhile the Lincoln Tunnel, not great back to Jersey but still your best option. And the GW Bridge your worst possible option. Thirty to forty minute delays, and that’s just going into town. Lower level closed, upper level all you get. Then back to New Jersey every approach is fouled-up: West Side Highway from the 150’s, the Major Deegan, the Bronx approaches and the Harlem River Drive are all a disaster, the Harlem River Drive could take you an hour, no direct access to the GW Bridge with roadwork. And right now across the East River 59th Street Bridge, you’ve gotta steer clear of that one. Midtown Tunnel, Triboro Bridge, they remain in better shape. Still very slow on the eastbound Southern State Parkway here at the area of the, uh, Meadowbrook there’s a, uh, stalled car there blocking a lane and traffic very slow.

Just about every weekday morning of my life between ages six and eighteen, I listened to traffic reports exactly like this one sputtering out of my father’s battery-powered radio. And I do mean exactly: it was 1010 WINS that he had on every morning, with traffic updates every ten minutes from Pete Tauriello, who is evidently still doing the traffic reports that Goldsmith is transcribing. (Actually, now that I think about it, there was definitely a period where my dad listened to WNEW’s Bloomberg Radio instead — another AM news channel financed, of course, by the man who would eventually become mayor of New York.) But in any case, Goldsmith’s block of text activated neurons I didn’t even remember I had, and it occurred to me that his work is rarely considered in terms of the specific times, places, and communities that it evokes. Critics tend to be concerned with what it means to copy something so banal word-for-word — to be concerned, that is, with the theoretical — and miss that perhaps what he’s trying to get at is the banal itself, rather than the philosophy that leads him to reproduce the banal.

My dad listened to that little battery-powered radio while shaving, and then would bring it with him into the kitchen to make breakfast for himself, me, and my brother. My mother didn’t really eat breakfast; she seemed to subsist on instant coffee and diet Pepsi until noon. When I was very young, I would hang around in the bathroom watching my dad shave and then follow him and the radio out to the kitchen. When I was older, I would endeavor to wake up as late as possible, but I’d still find myself downstairs in the kitchen shoveling cereal or Pop Tarts into my mouth in the cold dark morning while the radio chattered away. This was a decidedly pre-internet age; my dad listened to AM radio every morning so he could get the news efficiently, which I now suddenly recognize as an antiquated practice. I doubt he listens to that radio at all anymore, now that he has an iPhone. Stations like 1010 WINS are on a very short loop — the traffic and weather recur every ten minutes (and each time are just the slightest bit different, as conditions progress) and the material between these reports varies a bit more — sometimes you’ll get financial news, sometimes political news, etc — but even so, you don’t have to listen to the radio for more than twenty or thirty minutes before you start hearing the same stories repeated exactly. So it was always a little bit of a mystery to me why my father let the radio accompany him through his whole morning ritual — he, and I by extension especially when I was young and following him around, would be subjected to not just repeated-with-a-difference content like the traffic, but actually verbatim repeated content.

In addition to being repetitive, a lot of the news on the radio didn’t really affect my dad very much, and it certainly didn’t affect me. My parents had some investments, so I guess the financial news was sort of important, and it’s also how I learned about the stock market myself. (“Dad, what’s a ‘bear market’?”) The traffic reports that came on every ten minutes meant nothing to anybody in my family, since both of my parents had “commutes” that were less than ten minutes long. But listening to the traffic reports every morning taught me a fair amount about local geography — the BQE, the Major Deegan, the Verrazano — these names were burned into my brain before they even really meant anything, and years later when I learned to drive and started navigating the highways myself, I found myself having little a-ha moments every time I crossed a bridge in real life that I had previously only known from Pete Tauriello’s traffic reports.

Now that I think about it, the reason the traffic reports are so burned into my brain is that the one thing I personally was always interested in was the weather report, and these radio stations of course do “traffic and weather together” — so when you started to hear the traffic report, you’d hush everybody up so you could catch the weather. The thing about these news stations is that they operate at a blinding pace — everybody is always speaking very quickly so they can cram as much information as possible into their minute-long slot. The rhythm and diction of the traffic reports that Goldsmith transcribes are at least as evocative for me as the names of the tunnels and bridges. Some phrases the announcer seemed to have by rote — “stalled car blocking a lane,” “only one lane getting by” — these we’d hear several times a morning. “Jackknifed tractor-trailer” was one we’d hear a lot, and I remember being somewhat enamored of the sound of the words as well as slightly alarmed by its frequency given what an enormous disaster a jackknifed tractor trailer in fact is. Sentences in this barrage of information tend to be clipped and lack verbs: “Meanwhile the Lincoln Tunnel, not great back to Jersey but still your best option. And the GW Bridge your worst possible option. Thirty to forty minute delays, and that’s just going into town.” And to make matters worse, the announcers would jump all over the map: “then back to New Jersey every approach is fouled-up.” I remember trying to hold it all in my head, to picture the places they were talking about, and I always found that it was too difficult to follow. On the rare occasions that we did need the traffic report’s wisdom, we found that we’d have to strain to pick out the relevant information from this rapid barrage. But colorful touches like “the Hudson River horror show” remind you that there’s a person and a personality on the other end of this deluge of information that is so particularly stylized. I hadn’t thought about Pete Tauriello in years — in fact, I never really thought about him; I just heard his name a lot — but when Marjorie Perloff mentioned him in her chapter on Traffic in her new book, Unoriginal Genius, I gasped aloud as the “Pete Tauriello” neurons in my brain started firing again more than ten years later.

In retrospect, I think my dad probably just liked the chatter. The radio made us all feel connected to the outside world, whether or not we were paying very close attention to it. Now, of course, we have the internet to fill our lives with chatter and connection — but I think one of the things we can learn from Goldsmith’s Traffic is that not all forms of chatter are alike. Ten years from now, will radio announcers still be clipping their diction and dropping their verbs to fit all the traffic into their one-minute report? Or will news radio wither and die from the internet’s competition? Even if it doesn’t entirely vanish, I’d wager that news radio will reach ever smaller — poorer and older — segments of the population, and that it will no longer be a mainstay of middle-class suburban houses like my parents’.

I think, then, that part of what Goldsmith is getting at in his transcription projects is the power of records of utterly banal minutia to evoke the particular places and times from which they emerge. I doubt that Traffic would have had so powerful an effect on me if I hadn’t moved across the country to southern California, where names like “the BQE” make me feel nostalgic and the very idea of straining to hear the weather report in order to choose appropriate clothing is somewhat quaint. Neither the radio nor even weather itself is much a part of my life these days. But I experience these traffic reports as microcosms of a life I once lived, reflected through something I never particularly paid attention to while I was living it. Traffic reports — and weather reports, and newspapers, subjects of some of Goldsmith’s other transcription projects — are part of the texture of the everyday; they are where we live without noticing that we live there.

Now You Try

September 29, 2010 at 3:31 pm | Posted in contemporary, poetry | 4 CommentsI am a scholar of, teacher of, student of, and writer of poetry. This constellation of identities means that when I pick up a new book of poetry, I turn into Robert fucking Langdon from the fucking Da Vinci Code: I look for correspondences, connections, patterns, “Symbology,” so that I can solve the book’s mystery and come up with a thesis clever enough to bring down the Catholic church. Mike Young’s We Are All Good If They Try Hard Enough stumped me for a long time. There are no correspondences, there is no Symbology, there is just stuff and stuff and more stuff:

All the new bewilderment is about hay fever tablets.

In this it resembles the blind men running from the

elephant. In this it resembles nude appliance repair.

We’re pulled aside and told we’re loved, but listen:

the mustard gas has got to go. If I keep feeling this way

I will have to use a lot of emoticons.

The emoticons line is brilliant, but otherwise this passage is, well, kind of bewildering. The first line is intriguing and reads almost like a word-substitution game, but I can’t even imagine what it would mean to try to explain the “resemblances” noted in the second and third lines. I can make sense of the mustard gas as hyperbole, an apocalyptic version of “I love you, but lose the mustache,” but its relation to the earlier lines is utterly opaque.

My inner Robert Langdon was tearing his hair out until I told him to shut up already. This book is jam-packed with delightful moments, and it’s right and good and interesting that they’re moments instead of coy pieces of a picture-puzzle. “Dancing is just putting yourself on inside out.” “Oh, this is no cello analogy // you weepy motherfucker.” “In 1954, the last documented case of / ‘real people’ buried a milkshake recipe / and two coupons for used boxing gloves / outside Sparks, Nevada.” This book is a riot of noise and joy and weirdness, and reminds us that life is full of interesting things.

But then suddenly, three-fourths of the way of through the book, my inner Langdon found the Cryptex. In case you’ve forgotten or repressed this movie (which I swear I saw only in the dollar theater and only because it was such a cultural phenomenon), allow me to remind you that the Cryptex was the little cylinder with symbols on it that operated like a bicycle-lock and opened up to contain some kind of scroll that helped Tom Hanks solve all the mysteries. My Cryptex to Young’s book is a prose poem called “Now You Try,” and it begins like this:

Your roommate has something to tell you about the sociology of chip brands. Driving has something to tell you about shivering. Your porch has something to tell you about your ex-girlfriend. Evolution has something to tell you about acne. Bea Arthur has something to tell you about drugs. Beaches have something to tell you about community. Your mom has something to tell you, sometimes. The post office has something to tell you about the rest of your life.

It goes on for quite awhile, and it gets weirder:

If you are lying in bed and there is a maple bonbon on your nightstand a little out of reach, how much and what kind of effort you employ through your body toward that bonbon has something to tell you about death. 4AM has something to tell you, but it’s outside. The press has something to tell you they saw, but they always wait until it’s gone. Watermelons have something smart to tell you. Breakfast has something to tell you about your friends. The Decemberists have something to tell you about Russian history — yeah, you and everybody else, dude.

And so on and so on. And suddenly it all seemed clear: it’s not just that this is a book full of weird stuff, it’s that it’s a book full of weird stuff that means stuff. Everything has something to tell you if you know how to listen, and this, I think, is part of what Young is trying to tell us. The title of this poem, “Now You Try,” not only references the title of the volume (correspondences! Symbology!), but it invites the reader into this enterprise. The “formula” of this poem becomes rapidly clear, and the reader is asked to make up similar statements of her own, to look around and figure out which objects are trying to speak.

One thing that’s striking about this volume is that over half the poems are dedicated to specific people. In those poems and elsewhere, moments of real tenderness shine through: “This feeling is called kiss me. This feeling is called hi.” “The word okay is like skydiving. / If I say swingsets, will you make it rain?” “Give me something to give into. / It will be weird. It will be so weird.” These flashes of quirky sincerity put me in mind of Frank O’Hara, whose name I actually scribbled in the margins when I read these lines: “My moments of inward congratulation are / offset by meals alone in pants I really like.” If O’Hara is a patron saint of this volume, it is because he and Young both seem to be giving you a sidelong glance, revealing the marvels of the everyday while checking to make sure that nobody is taking themselves too seriously.

So if you like weirdness — if you like Craigslist, Leonard Cohen, and stray flamingos — if you hate the damn Da Vinci Code — you owe it to yourself to pick up We Are All Good If They Try Hard Enough and to ready yourself for Mike Young’s forthcoming fiction collection, Look! Look! Feathers.

Mostly Everyone Loves Some One’s Repeating: Gertrude Stein and Lost

May 25, 2010 at 11:41 pm | Posted in attention, love, poetry, pop culture, publication, repetition | 2 CommentsFirst of all, this is old news to most of you who know me personally, but all of you in blog-land might be interested to know that I’ve got an article published on H.D.’s Trilogy, her WWII epic poem, and her seances in which she talked to dead RAF pilots. It’s in the Journal for Cultural and Religious Theory’s most recent issue, and it’s called “‘An Unusual Way to Think’: Trilogy‘s Oracular Poetics.” You can download & read the PDF for free. Yay for the information age!

If you’ve been starved for my friendlier, less academic prose (and what follows below is not enough to slake your thirst), you can also check out the poetry reviews that I recently did for Noö Journal — mine are the first two pieces in the magazine, actually, linked there on the upper right.

Okay, on with the show. In what follows, as the title of this post promises, I will talk about Gertrude Stein for awhile and then I will make some connections to the series finale of Lost, because I am a dork. I will put that section behind the fold, for the spoiler-conscious, and I will endeavor to make the first part of the post worthwhile in and of itself. I will also try to make the section on Lost as general and thematic as possible, so that you can read it and get something out of it even if you haven’t watched the series.

Because I am an immensely unwise person, I have decided that my dissertation requires me to read Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans, a 925-page-long reputedly incoherent tome which is actually blurbed with the following line from the New Yorker: “The first stunningly original disaster of modernism.” But to my great surprise, I am enjoying the hell out of it. Here is part of the section with which I am currently madly in love. I quote at some length so you can get the effect of her prose, but please do try to read this attentively, because the nuances are important:

Every one is always repeating the whole of them. Always, one having loving repeating to getting completed understanding must have in them an open feeling, a sense for all the slightest variations in repeating, must never lose themselves so in the solid steadiness of all repeating that they do not hear the slightest variation. If they get deadened by the steady pounding of repeating they will not learn from each one even though each one always is repeating the whole of them they will not learn the completed history of them, they will not know the being really in them.

As I was saying every one always is repeating the whole of them. As I was saying sometimes it takes many years of listening, seeing, living, feeling, loving the repeating there is in some before one comes to a completed understanding. This is now a description, of such a way of hearing, seeing, feeling, living, loving, repetition.

Mostly everyone loves some one’s repeating. Mostly everyone, then, comes to know then the being of some one by loving the repeating in them, the repeating coming out of them. There are some who love everybody’s repeating, this is now a description of such loving in one.

Mostly everyone loves some one’s repeating. Everyone always is repeating the whole of them. This is now a history of getting completed understanding by loving repeating in every one the repeating that always is coming out of them as a complete history of them. This is now a description of learning to listen to all repeating that every one is always making of the whole of them.

A large part of The Making of Americans is essentially a typology of characters — Stein attempts to describe different “types” of people who live in America. This concept is what she is introducing at the end of this passage; the narrator is someone “who love[s] everybody’s repeating,” and has listened sufficiently to everybody so as to piece together a “complete history” of all of them.

But let’s back up. What does it mean to say that “every one is always repeating the whole of them”? First of all, there’s the sense of verbal “repetition,” which of course this text itself enacts. We all have favorite stories about ourselves to tell, favorite topics to discuss, frequent refrains in our daily accounts of ourselves. I presently have a semi-regular non-appointment with a friend of mine for what generally turn out to be quite long conversations about our presents and pasts. He is a relatively new acquaintance, which means I get to trot out some of my “greatest hits,” and have thus had the opportunity to examine this particular(ly narcissistic) pleasure. It’s the pleasure of a well-told story as much as of a well-lived life; I admire myself for both the events and their recounting equally. Because of course for me, these stories are already repetitions, benefiting from earlier tellings. But I worry that some of these stories have stopped being “authentic” because they have been told so many times, and that I might not be giving my interlocutor as much attention as he deserves by launching into these rhapsodies as often as I do. (Speaking of favorite themes, see this post for an earlier meditation of mine on personal anecdotes and the authenticity thereof.) But Stein loves repetition. She would tell me, I think, that repetition makes my stories more authentic, in the sense that as I refine them, they become more perfect expressions of myself. Not only do they become better vehicles for conveying whatever truth about myself inheres in stories about — for example — my summer jobs in high school, but they become better entertainment for my interlocutor, and I think this latter function should not be overlooked.

So there is verbal repetition — but there is also, like, life repetition. In a mundane sense, we all have schedules. We all have approximately set times when we wake up and when we go to sleep, most of us have some kind of official work schedule we have to abide by, and many of us have more or less ritualized ways that we use our spare time: we go to the same couple of lunch places, we unwind at the end of the day with a beer and The Daily Show, whatever. In a more profound sense, most of our lives are shaped by broader patterns of repetition: the same damn relationship hang-ups playing out again and again, the same nonsense day in and day out from your mother that you thought you both would have outgrown by now, etc. Freud’s concept of Nachträglichkeit is also about repetition — according to this theory, certain traumatic events leave us numb because we are unable to process them, but then later (often much later) in life, a seemingly unrelated stimulus can set off an emotional reaction out of all proportion with the stiumulus itself, because this reaction is the result of much-belated emotions connected to the original traumatic event.

What I like about Stein’s formulation (“every one is always repeating the whole of them”) is that it levels all these senses of repetition, from the echoing effect of profound emotional trauma to your verbal tics and your morning coffee ritual, and says that in all of these repetitions you are repeating “the whole of [you].” It reminds me of fractals, geometric drawings made up of pieces that are each smaller-sized copies of the whole. We all, I think, worry about the degree to which our lives our repetitive. Most of us have escape fantasies, whether or not we have any actual desire to act on them. Maybe I read too much Jack Kerouac as a teenager, but I suspect I am not the only person who sometimes fancies that she could be living a better and freer and more authentic life if she could just summon the courage to quit her job and hit the open road. What Stein does here is show us that repetition is authenticity — we can’t escape it even if we try. If we didn’t have desires that lead us to the same perfectly-calibrated cup of coffee every morning, or habitual turns of phrase that are uniquely our own, then who would we be?

The counterpart to this is the theory of love that Stein espouses here: “Mostly everyone loves some one’s repeating.” This is, by necessity, a theory of long-term love. She reminds us that “sometimes it takes many years of listening, seeing, living, feeling, loving the repeating there is in some before one comes to a completed understanding.” If repetition is authenticity, then repetition demands attention — not boredom or disengagement, which might be our more automatic responses. Importantly, Stein recognizes that the repetition in our lives is never exact repetition, though it may look that way to outsiders. Love, for Stein, becomes paying attention to the nuances of somebody’s repetitions. Change does not always happen drastically — in fact, most change in our lives probably occurs at a gradual pace, as a matter of drift in a series of repetitions rather than as a radical break. And what is sharing your life with someone if not the process of gradually letting your repetitions overlap and shape one another?

This is the part where I’m going to start talking about the television show Lost. If you’ve been watching the show but haven’t seen the finale yet, you should probably stop reading. If you’ve never seen it and/or have only vague plans to watch it someday, you can go ahead and continue, because I will not reveal any answers to any mysteries; I’m just going to describe the kind of emotional closure that the show gives us while avoiding specifics as much as possible.

Continue Reading Mostly Everyone Loves Some One’s Repeating: Gertrude Stein and Lost…

The New Sincerity: On Daniel Bailey’s Drunk Sonnets

December 4, 2009 at 2:05 pm | Posted in contemporary, flarf, irony, poetry, sincerity | 10 CommentsHuge swaths of the American population have always been into sincerity: Christians. Truckers. Moms. Emo kids. But since the early 20th century, anybody who’s identified as “cool” — with the exception of emo kids and arguably of hippies — has thrived on ironic distance. But as anybody who’s been tracking hipster culture lately knows, we are currently going down a rabbit hole in which irony is trying so hard that it’s turning into sincerity before our very eyes. Case in point: Daniel Bailey’s The Drunk Sonnets, recently out from Magic Helicopter Press, a triumph of postironic poetry and a harbinger, perhaps, of the world to come.

Now, the hipster ironists of the poetry world are the Flarfists, whose blog features a giant unicorn and the slogan “mainstream poetry for a mainstream world.” But of course, their poetry is anything but mainstream — it is assembled from the detritus of the internet as targeted through google searches, and it is nothing if not hostile to interpretation. Flarf poetry is extremely resistant to sincerity, and even to communication. It’s a parody of poetry, and a parody of the internet, and if sentiment does creep into Flarf poems it’s with invisible quotation marks around it, as in this excerpt from “Spanksgiving,” recently reposted for the holiday:

Now Ride! By now a lot of people are showing

up for their holiday weekend in the desert. A large

contingent at the retail store for “Leather Happy Hour.”

Spank hard…spank safe!

The only Turkeys I’ll be seeing this Spanksgiving are my dear

friends Brook, Katie and Baby Richy. I was very happy

to help them mark this moment in their family’s growth.

Spank hard…spank safe!

We got lots more smut in store for you all month long!

(And on a school night, nonetheless!) I had to kill

them to make them happy or some shit.

The middle stanza drips of sincerity and is probably a real excerpt from somebody’s blog except for the poet’s substitution of “Spanksgiving.” But the “spank hard… spank safe!” refrain and the bondage/smut references in the adjacent stanzas make it clear that we are supposed to smirk at the sentiment. The “mainstream poetry” Flarf slogan may be meant to indicate that the vapid and absurd internet material that the Flarfists draw from IS the mainstream now, and if their poems end up being more scatalogical and incoherent than most “mainstream” people can deal with, then maybe those people should learn to face up to the reality of their own culture. But slapping “mainstream poetry for a mainstream world” on your avant-garde poetry website might just as easily be read as hipster posturing — the equivalent of wearing a Journey T-shirt to an Animal Collective concert and challenging people to wonder about whether you really listen to Journey and whether you would be more cool or less cool if you did.

On the surface of it, Daniel Bailey’s The Drunk Sonnets (and the multi-author blog on which they were first posted), have a lot in common with Flarf. All Drunk poems, both in the book and on the blog, are written in all capital letters — the international internet language of idiocy and/or assholery. Like Flarf poems, Drunk poems feature inanity, banality, and frequent topic shifts and interruptions. But unlike Flarf poems, there is real emotional content in Drunk poems. Bailey’s book consists of real live sonnets — most of them are Italian sonnets, with an octave and a sestet and a turn and everything — describing the speaker’s alcohol-drenched misery following a breakup. Here’s one of my favorites:

Sonnet 14

IF ANYONE KNOWS WHAT IS GOING ON EVER THEN HEY

I AM HERE IT WOULD BE NICE TO TALK SOMETIME

INFOMERCIALS HAVE STARTED AND I KIND OF WANT TO DIE

I’M PRETTY SURE THIS ONE IS ACTUALLY FOR A MORGUE

OK SO ACTUALLY IT’S FOR THE BIBLE OR SOMETHING

SO IT’S A COMMERCIAL FOR TRYING TO BE HAPPY OR SOMETHING

BUT I AM NOT HAPPY TONIGHT NO I AM NOT JUST HERE

IF HAPPINESS EVER WORKED THEN HOW — I DON’T KNOW

HAPPINESS IS A LIZARD IN THE SUNLIGHT GETTING WARM

AND THEN IN THE NIGHT BENEATH A ROCK EATING FLIES

AND SWALLOWING THE MEAT OF THE TRASH OF THE DIRT

AH, SO TONIGHT IS A LITTLE DRUNK AND OK OK OK

THAT IS GOOD SO LET ME BE — THERE IS NO LOVE TONIGHT

GOD IS LIKE BONO — SOME DICKWAD NO ONE WILL EVER MEET OR LIKE

The poem begins with a sort of open-ended plea that reflects the internet age in its very vagueness. Most Facebook and Twitter updates are not addressed to anyone in particular; they are just thrown out into the abyss and we hope that some of our friends will respond. This diminishes our responsibility for our own feelings as well as potentially diminishing the intensity of our relationships; instead of calling a friend to vent about a problem, you can just post a vague allusion to it on your Facebook and receive a bunch of vague support from whatever acquaintances happen to have logged on in time to see your post. In this poem, there is real pathos in this vagueness : “IF ANYONE KNOWS WHAT IS GOING ON EVER THEN HEY / I AM HERE IT WOULD BE NICE TO TALK SOMETIME.” This is a person who is lost and lonely. In the last line of the first stanza, the speaker appears to be able to laugh a little at his own misery — “I’M PRETTY SURE THIS ONE IS ACTUALLY FOR A MORGUE” — but in the next stanza his joking façade cracks, and he says straight out that he’s unhappy.

Then suddenly, in the first stanza of the sestet, there is a total change of tone from the banal to the imaginative. The lizard seems to be a figure for the banal — feeding, as it does, on the “meat of the trash of the dirt” — but it is at least a figure in a poem that until now has been aggressively anti-poetic. I don’t think it’s exactly a metaphor; I don’t think the speaker is saying that happiness is LIKE a lizard, but rather that only simple things like lizards are happy. It’s the same construction as “happiness is a warm gun,” and I think the use of “warm” to describe the lizard might not be an accident. After this little reverie, the speaker realizes he is drunk, makes temporary peace with his loneliness, and curses God. The tone switches back to banal rambling, but the God = Bono simile betrays a wry poetic sensibility that few drunks (who aren’t poets to begin with) are capable of.

What gets me so excited about Drunk poetry as written by Bailey and friends is that it breaks down the pervasive assumption that experimental form is incompatible with emotional content. That this assumption exists baffles me, since Joyce’s Ulysses stands as an enormous and wildly famous testament to the contrary, but I have observed it in many (though not all) of my students, my colleagues, and the scholars in my field. Most importantly, I have observed it in the experimental poets of today, many of whom seem content to be tricksters and treat “feelings” as counterrevolutionary.

That’s not to say that Bailey’s sincere moments are always delightful, however. The breakup theme gets tedious (and maybe that’s intentional?), and the poetry is frequently at its wretched worst when he is at his most sincere: “I LICKED THE SPOONS THAT WE HAD SCOOPED INTO OUR HEARTS / AND I GAVE YOU TWO SCOOPS EVERY TIME — I WASN’T CHEAP.” I mean, puke. Puuuuuke. But this is an interesting post-ironic moment. Is it a joke? When we puke at these lines, are we puking with him or on him? What about these lines?

I COULD PRACTICALLY RIP MYSELF APART

AND WHAT WOULD I EVEN FIND BUT YOUR LOVE

THAT I’VE SAVED UP LIKE CRUMBS

The hipster in me recoils at the naked sentiment — last night I marked these in my book as “puke” lines, but today they look kinda nice. And this oscillation, this indeterminacy, is precisely what is going to characterize the post-ironic age. I am not proposing that a return to Byronic levels of sincerity is imminent or even advisable, but that as we feel our way back from posturing in silly haircuts to occasionally being able to say what we mean, we are going to encounter a lot of weird situations that look a lot like Bailey’s poems. The trouble with foreclosing on the possibility of sincerity — as Flarf more or less does — is that you cut off a whole lot of interpretative possibilities. But if you do occasionally say something “real,” you open up the downright dangerous possibility that anything in your poem might be “real.”

It’s not an accident, though, that Bailey & friends have adopted drunkenness as their aesthetic banner. The speech of drunk people is frequently a fascinating blend of comedy and sincerity, and it moves in and out of self-awareness pretty fluidly. One minute your drunk friend will be saying something absurd, the next minute he’ll be telling you that you are truly one of his best and most excellent friends, and in another minute he’ll be laughing at himself and telling you how drunk he is and not to listen to anything he says. The fact that Bailey’s speaker is drunk allows him to be sincere with relatively little risk; we know that our drunk friends’ resolutions generally come from genuine feelings, but at the same time we’ve learned to take them with a grain of salt.

So it appears that the Drunk poets get to have their cake and eat it too, which leaves us with just one burning question: are they really drunk, or are they writing in “drunkface”? Fred Astaire claimed in his autobiography that he knocked back two shots of bourbon before the first take of the famous drunk dancing scene from the 1942 musical Holiday Inn, and one before each successive take — and they got it on the seventh take. This scene alone is worth the price of admission; Astaire achieves a balance of grace and sloppiness that could perhaps have only been executed by a legitimately drunk professional dancer. But what about Zui Quan, the form of Chinese martial arts known as “Drunken Boxing” popularized by Jackie Chan’s Drunken Master films? Though Jackie Chan’s character is portrayed as actually drunk, real Zui Quan practitioners say that you need to be sober in order to have the balance and coordination necessary to perform the staggering, fluid motions that are merely meant to imitate drunkenness.

Here’s where I go off the conspiracy-theory deep end: Sam Pink, in one of the blurbs on the back of the book (which by the way are the two greatest blurbs I have ever read in my life), refers to “the midwest sadness embedded as deeply in [Bailey] as his Kool-Aid moustache,” and indeed, Bailey’s author bio claims that he is from Muncie, Indiana. You know who else is from Muncie? Tim Robbins’ character in The Hudsucker Proxy, a naïve midwesterner who accidentally finds himself in charge of a big-city corporation. When the femme fatale wants to gain his trust she claims to be from Muncie too, which involves an elaborate lie including singing the Muncie High fight song along with Robbins by following him a half-beat behind and being able to guess about the predicable rhymes. When her betrayal of Robbins is eventually revealed, he’s so naïve that all he can say is “I can’t believe I was betrayed by you….. a Muncie girl!”. So maybe — just maybe — Bailey’s alleged Muncie origin is a winking reference to an absolute sincerity that is, itself, ironized in the Coen Brothers’ film.

So is he really from Muncie? Is he really drunk? Does he sincerely want you to lick the spoon he has scooped into his heart? I don’t know, but I’m having fun trying to figure it out.

The Dogs on Main Street Howl

August 27, 2009 at 10:31 pm | Posted in personal, poetry, travel | 3 CommentsAs you have no doubt noticed, I’m having a hard time figuring out what to say to this blog lately, since my academic thoughts are all getting funneled into my dissertation. But two out of my three most recent posts have been collage-poems, so I figure I may as well share with you another poem in order to keep this place from going completely dark. Lately in places other than this blog I have been experimenting with another poetic technique of constraint, wherein I take every Nth letter of an existing, usually rather famous poem, and write a new poem connecting those words in the order that I found them. The best results of this I have been hoarding with the ambition of getting them published someplace, but tonight’s poem hits that place between “potentially publishable” and “do not show to anyone ever” that blogs so happily occupy — and besides, I think it’s kind of fun. Instead of a poem, I used “The Promised Land,” one of my favorite Bruce Springsteen songs, as my source text, because it’s my last night in Jersey until December. Enjoy.

—

Thirty miles into Utah and the

radio stops working. Barefoot driving

turns me part machine; soon the cops won’t know

who to tell to step out of what. They all said to live

in the moment, like a moment was a place where you could

wipe your feet and hang your hat. I don’t know anymore

what I’ve done, just that I’ve got a long way to go.

Your eyes can’t tell when somebody’s gone cold-hearted, so just

remember this: when you get cut and somebody else bleeds,

the dogs understand. Cut yourself into ribbons,

boy; believe in the dark spaces between them.

I’m heading straight for the twister,

so either you’ve gotta blow apart

your tomorrows or you’ve gotta leave the keys

in the ignition. They all said to live in the moment

like a moment was a goddamn split-level condo.

I believe in starting fires and running

for the horizon.

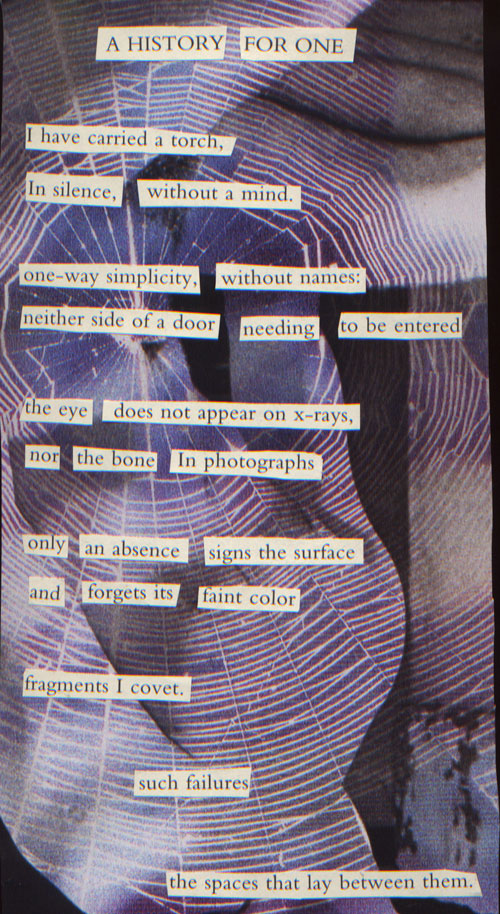

A History / For One

July 24, 2009 at 8:21 pm | Posted in collage, poetry | 2 CommentsReaders of this blog (with relatively long memories) may be interested to learn that I have just finished teaching a class on sacrifice, something I started to think seriously about two and a half years ago. I proposed the class over a year ago, and have been offered two chances to teach it since then, both of which I had to turn down because of other, more attractive teaching offers. This summer my number came up again and I was thrilled to finally get a chance to do it. The class went wonderfully, and my students were shockingly good, but teaching what’s supposed to be a ten-week course in a five-week summer session ate up all of my dissertating time. I taught the last class two days ago, finished grading their second-to-last papers yesterday, and found myself this morning facing a one-day-long chunk of potential dissertating time — because the drafts of their final papers start coming in tomorrow.

And I rebelled. “One day,” I said to myself, “is barely enough time to reacquaint myself with my notes and get back into the headspace of even thinking about this chapter. And then tomorrow I’ll have to start reading drafts again. I can’t possibly do real work today.” So instead I wrote a poem, using the same collage method I used on the one I posted in March. (In fact, it’s made from leftover words from the previous and certainly better poem, which is part of why there are so few concrete images here — I used up all the good ones on my first effort.) I’m starting to come to terms with the fact that collage really might be where my poetic voice lies. It’s just so damn hard to say anything in this post-ironic day and age. This blog is painfully sincere a lot of the time, and I’m always sort of amazed that nobody makes fun of me for it — my theory is that my entries are so long & academic that only people who genuinely care about me and/or what I have to say even make it to the end of most of them. (Hint: the end is always where it gets sappy.) But even though I’m (almost) capable of maintaining a blog that is very sincere about literature, I quail before the idea of writing a poem that says something about myself in anything like a straightforward manner. It’s not that I have burning feelings that I am afraid of putting into words, either — I’m not sure that I’ve experienced that particular kind of angst since I was about twenty years old. Rather, what excites me about poetry these days is the idea of letting the words tell their own stories — of hunting those stories out, sifting among fragments and letting them cohere and settle until they find a shape that I can call a poem.

All of that is basically to say that I utterly disown any gothy melodrama that the poem below may exude. The words, it was their idea.

20 books

March 7, 2009 at 2:42 pm | Posted in personal, poetry | 3 CommentsHere’s a meme I picked up from Ron Silliman’s blog: list the 20 books that caused you to fall in love with poetry. It is, as Ron notes, quite a different proposition from asking you to list the 20 books of poetry most influential on your current thinking. My list is pretty weird, shaped largely by what I happened to come in contact with during high school, and by a particular class I took in college which cemented my certainty that experimental poetry was What I Was Going To Do With My Life. Here’s the list in alphabetical order, with some explanatory notes.

Will Alexander, Asia and Haiti — I decided to write a paper about this in that class because it was the most difficult book we’d read so far. Making that decision made me feel pretty cool.

John Ashbery, Your Name Here — A peculiar choice from Ashbery’s oeuvre, to be sure, but it was the first book of his I ever came across. “The Fortune Cookie Crumbles” remains one of my favorite poems ever.

Karin Boye, Complete Poems, tr. David McDuff — This was sent to me by my cousins in Sweden, and it was exactly what a melodramatic teenager needed. Her poems are a strange marriage of strong viking spirit and burning romance. Here are some lines that stick with me to this day: “Fair, fair is joy, fair also is sorrow. / But fairest is to stand on pain’s battlefield / with stilled mind and see that the sun is shining.”

Reggie Cabico and Todd Swift, eds., Poetry Nation: The North American Anthology of Fusion Poetry — I bought this book at Barnes & Noble when I was about fifteen because I wanted to find out “what people were writing today,” and I was so charmed that I read at least four or five of the poems in here at an event at my high school. I think the major revelation that the book gave me was that poetry could be really fucking funny without being trivial, a fact that would be reinforced by all the experimental stuff I would begin reading once I got to college. A few years ago, Cabico was brought out as a special guest at a poetry reading I’d participated in, and it seemed like I made his year by recognizing him and explaining at great length what his anthology had meant to me.

e.e. cummings, 100 Selected Poems — A friend of mine once said that e.e. cummings is for deep sixteen-year-olds, and I think he’s right, but I think a lot of us are secretly deep sixteen-year-olds at heart. When I was a deep sixteen-year-old in the flesh, I would stay up late and sit on the floor in front of the full-length mirror in my closet and read e.e. cummings out loud to myself. The revelation that cummings was not actually very difficult once you read him out loud was a pretty important one for me.

Emily Dickinson, Selected Poems — A boy gave this to me for my sixteenth birthday, with a bunch of artifacts inside keyed to specific poems — pictures, magazine clippings, a necklace. Most of them are still in there. Years later, I would write a paper about death and the void in Dickinson, and decide that this gifted edition presented a pretty heavily edited view of her work.

Allen Ginsberg, Howl — Sooner or later, every poetry-loving teenager gets ahold of Howl. I was fortunate enough to have access to my mother’s legitimately-70s copy. Later, I would name one of my notebooks “The Sunflower Sutras.”

Joy Harjo, A Map to the Next World — I read this book in college under my favorite tree on one of the first warm days of spring, and cried like I was waking up from a terrible dream. Just a few days ago I was reminded of that experience and I picked the book up again, and I had trouble figuring out what had moved me so deeply. Harjo has some interesting things to say, for sure, and I’ve always been interested in myth, but I think it must have been a confluence of circumstance that made me love this book so much back then.

H.D., Trilogy — I have now written four separate papers on this book for graduate school. Every time I re-read it there’s something new to pay attention to.

Lyn Hejinian, My Life — This is one of the books I wrote my senior honors thesis on, and I read it six million billion times. I circled all the repetitions and keyed them together by page number, I underlined any time she seemed to be saying anything about the composition process, and I came to love parataxis above all other literary devices.

Yusef Komunyakaa, Neon Vernacular — I read “Woman, I Got the Blues” to basically everyone who will let me. You have to yell the “sweet mercy” line pretty loudly and sincerely to get it right.

Mina Loy, The Lost Lunar Bedecker — I was on a date with a guy ten years older and a million times cooler than I was, and I took him to one of my favorite little bookstores in NYC, and he pulled this book off the shelf and said “if you buy this, I guarantee that you’ll be ahead of the game in your next poetry class.” And he was right; Loy was assigned to me just a few weeks later, in a modernist poetry class I took my senior year. I had already read it and fallen in love with “Songs to Joannes,” which remains one of my favorite ambiguous-love poems of all time.

Harryette Mullen, Sleeping with the Dictionary — This was it; this was the book that I was reading when I decided “this, right here, is what I am going to do with my life.”

Pablo Neruda, Selected Poems, A Bilingual Edition, ed. Nathanial Tarn — Really, what I loved the most in this volume was the Viente Poemas de Amor. I read my mother’s copy so many times that the binding fell apart, so she didn’t mind too much when I stole it and brought it to college with me.

Sylvia Plath, Ariel — I am allergic to bees, and hence pretty afraid of them. My most vivid memory of this book is of being so unable to put it down that I took it to the dorm kitchen with me to read while making dinner.

Adrienne Rich, The Fact of a Doorframe — I first encountered Rich through one of her more recent books assigned in class, but it was this “selected poems” volume that really had an effect on me; watching the arc of her career as it developed was incredibly interesting.

Leslie Scalapino, The Public World / Syntactically Impermanence — My most vivid memory of reading this is of lounging around on the quad in the sunshine while a tour group walked by, and thinking to myself, “The scene of me reading here only looks idyllic. If they could see inside my head or even just onto this page, boy howdy would they get a different idea.”

Juliana Spahr, Fuck You – Aloha – I Love You — I read this book at the beginning of a five-hour bus ride, and then I read it again, and then I read it again. It was like watching the same tower be built, unbuilt, and rearranged over and over again.

Gertrude Stein, Tender Buttons — The professor of that landmark poetry class I took in college gave us the first few pages of this on the first day of class, and I thought he was out of his mind. Over the next few weeks, though, I realized that he was right, and this stuff was incredibly interesting. Furthermore, when I read the whole book, I was surprised to find that it was downright hilarious. Now that I’m a teacher myself, I too start my poetry classes with Tender Buttons. (And Shakespeare, and Christian Bök’s aural ravings, and I ask my students whether each of these three objects count as poetry and why.)

Rosmarie Waldrop, Reluctant Gravities

Rosmarie Waldrop, The Reproduction of Profiles – Waldrop instantly became my favorite living poet when I read these two books, and she remains so today (her other books are great, too). I think she is the only person in the history of the human race who has successfully solved the mind-body problem.

Here is a poem

March 2, 2009 at 3:45 pm | Posted in poetry | 9 CommentsLast night, in a fit of boredom with my dissertation reading, I decided I needed to make something. I have a bunch of back issues of Poetry, the incredibly dreary magazine of the Poetry Foundation, an organization whose website invites you to “discover poetry” via the six essential categories of “love,” “weddings,” “autumn,” “sadness,” “death,” and “funerals.” (I once got so livid about this fact that I wrote a sestina with those six categories as the end words, but it wasn’t very good so you don’t get to see it.) Anyway, I came into these back issues of Poetry in college, when one of my professors was getting rid of them and I thought that reading them would be a good way to figure out “what was going on in the poetry world.” But I figured out quickly that Poetry is about as on the cutting edge as the Grammys, which recently gave “best rock song of 2008” to Bruce Springsteen’s “Girls in Their Summer Clothes.” I grew up in New Jersey and I love The Boss, but that song utterly fails to rock — and there are plenty of yowling young bands with questionable haircuts that could teach him a thing or two these days.

So anyway, I cut apart the first one of those back issues last night, which required me to read it pretty closely. This was at times physically painful, but one unexpected result of scanning these poems for interesting words or phrases was that I noticed that of the fifteen or so poems in the magazine, at least five contained the word “mirror,” another five contained the word “river,” and another five were on the subject of aging. Furthermore, these groups overlapped somewhat and were arranged sequentially in the magazine — it began with “river” poems, then moved into poems where “rivers” were compared to “mirrors,” then “mirror” poems, then poems where people looked into mirrors & saw themselves aging, & finally moved into “old age” poems. These observations represent a general trend & don’t cover absolutely every poem in there, I don’t think, but I was somewhat surprised to see the organizing hand of an editor so clearly visible. However, ultimately, nearly all these poems were nothing but triteness and treacle. Do we really need more poems comparing rivers to mirrors? Come the fuck on.

These were my rules: I could use nothing other than material in this one issue (June 2003), and I was limited to what my scissors could actually remove. So if I cut out something on one page, and in doing so I mangled something on the reverse, that thing on the reverse page was lost to me. Furthermore, if I messed up in cutting something out and cut the word apart, it was lost to me. Rather than agonize over whether the poem on the front or the reverse of the page had “better” material for my purposes, I just went straight through the magazine page by page — which means, I suppose, that poems on odd-numbered pages are probably represented more heavily than poems on even-numbered pages. Fun fact: one of the poems that I harvested from was by Kay Ryan, our current poet laureate. It was called “The Niagra River,” and while not actively offensive to my sensibilities, it was pretty boring.

I apologize for the quality of this picture; for some reason it was really difficult to get the text to photograph legibly. Also, you might be interested to know that the picture at the bottom is from a Visa ad, and the whole thing is pasted on the side of a shoebox with an interesting texture that I found in my closet. Without further ado:

The Writer, the Fragment, and the Hedgehog: R.I.P. David Foster Wallace

September 14, 2008 at 11:01 pm | Posted in contemporary, fiction, love, poetry | 5 CommentsAs you probably already know if you are a literary type, David Foster Wallace has died. In the following thoughts about Infinite Jest, I will not divulge any plot details — but I will discuss the general shape of the plot arc in a way that, frankly, would have spoiled the reading experience for me in a pretty significant way if I had known it beforehand. However, if you’ve read even a single review of IJ, you’re probably already aware of the thing that I’m wary about disclosing; my reading experience was somewhat abnormally sheltered. Let’s put it this way: if this blog post were about The Usual Suspects, it would not tell you about the identity or even the existence of Keyser Söze, but it would tell you that the movie has a twist ending. (We all knew that, right? Sorry. I shed a lot fewer tears for watchers of a two-hour movie than for readers of a thousand-page book.) Anyway, this post will give you information about plot structure, but not about plot. The undeterred can continue reading below.

Blog at WordPress.com.

Entries and comments feeds.